AI Tsunami

Trent

During a recent Zoom faculty meeting, we were asked to discuss challenges we were experiencing in our classrooms and with students. This is college, so we are dealing with adults. In twenty years of teaching, I have rarely had problems until now. And that problem is Artificial Intelligence.

How do we manage this? My colleagues ask. What policies are in place to mitigate cheating? Is using AI even considered cheating? For three years, I have watched the AI tsunami drown academic integrity, erode critical thinking, and scatter learning and knowledge to the wind. Under its tectonic shift, AI is crushing creative thought and ideas. And it has just reached our shores. I wonder, What can I do?

I don’t have an answer to this question, and neither does the college nor the countless academic institutions throughout the country. One thing academia is good at is answering tough questions. We function as researchers, committees, and councils to investigate and resolve issues. As academics, we are held accountable to administrators and governing boards. So, when we hear the powers that be state: We are working on this, we get twitchy. Who is working on this? What am I to do in the meantime?

I am not here to point fingers or single out the college or other institutions grappling with these questions. Quite the contrary. There are plenty of people working on this. Smart people who are dedicating resources and their careers to these tough questions. But AI is like trying to seize a shooting star or a bolt of lightning using your fingertips.

Two years ago, which seems a lifetime ago, most AI-generated academic papers were clunky. The inconsistencies in logic, organization, grammar, and punctuation were dead giveaways. And students were contrite when caught. “I’m sorry.” They said. “I’m overwhelmed with class assignments.”

“Okay, let’s try this again,” I said. “I’m here to help.”

Not anymore. The use of AI is so ubiquitous that some students do not recognize the ethical issues with its application, especially when they are asked to refrain from using it. Sometimes, I can reach students who will eventually be taking state boards to become an RN or the PE exam to become an engineer. Speaking in broader terms, which had served me well for decades, no longer works. Reminding some students that higher education or training leads to the ability to discern information that helps in decision making, I sound like a wizard talking mumbo jumbo. How old are you, anyway? I see written on their faces.

Today, programs like ChatGPT, owned by OpenAI, spit out nearly perfect work, and the AI detector software that once helped professors spot AI-generated papers lags in the Dark Ages. The only way to know for sure if students are cheating is to ask them. But again, that begs the question: What is cheating? Plagiarism is cut and dry. It is the act of taking the words and ideas of another and claiming them as your own without giving credit to the original author. AI works very differently. Think of a monster brain the size of your house, or perhaps the town you live in. Stored in the brain is every conceivable algorithm available to answer a question, solve an equation, or, in my case, write a paper for an English composition class.

I asked ChatGPT to write a two-page paper about the relationship between Elisa and the Tinker in John Steinbeck’s short story “The Chrysanthemums” with three quotes and a Works Cited page, following MLA guidelines. Here is what I received in under fifteen seconds:

Elisa and the Tinker: A Complex Bond of Yearning, Power, and Deception

John Steinbeck’s “The Chrysanthemums” unfolds as a nuanced and emotionally charged encounter between Elisa Allen—a capable, passionate woman suffocated by her domestic world—and a traveling Tinker, whose feigned interest both ignites and shatters her fragile hopes. Their brief yet intense interaction reveals Elisa’s deep-seated longing to be seen, respected, and connected, while the Tinker’s manipulative charm exposes the harsh limitations placed on her by a society that undervalues women.

Elisa’s garden is more than a hobby—it is her sanctuary, an outlet for her suppressed potential. She tends her chrysanthemums with an almost mystical precision. Elisa explains how her hands work in harmony with the flowers: “They never make a mistake. They’re with the plant. Do you see? Your fingers and the plant… You can feel that, right up your arm.” mrlocke.net Her “planter’s hands” are a tangible expression of her creative power and self-worth—qualities unappreciated in her marriage, where her husband gently dismisses her competence by suggesting she work in the orchard instead mrlocke.netLitCharts.

When the Tinker arrives, Elisa experiences an electrifying shift. His attention awakens both intellectual and sensual energy in her. She nearly reaches out to him, whispering, “Every pointed star gets driven into your body. It’s like that. Hot and sharp and—lovely.” mrlocke.netLitCharts In that moment, Elisa is seen—not merely as a dutiful wife or gardener—but as a woman of feeling, power, and depth. The Tinker temporarily becomes her mirror, reflecting the fulfillment she craves.

But this brief connection is revealed to be illusory. The Tinker’s interest is nothing more than a business ploy: he wants work. The true depth of his deception is laid bare when Elisa later notices her chrysanthemum sprouts discarded on the roadside—“He might have thrown them off the road … But he kept the pot,” she murmurs, her voice wavering between realization and heartbreak. “He had to keep the pot.” LitCharts+1 This act becomes a crushing symbol: Elisa’s identity and passion have been used, stripped down, and discarded.

This encounter leaves Elisa poised between empowerment and defeat. She returns to her domestic role, dressing to appear “strong and happy” for her husband’s approval—but now the sheen covers a deeper sorrow. Steinbeck suggests that for Elisa, the Tinker’s deception is a betrayal not just of trust, but of her deepest self.

Ultimately, their relationship underscores a painful reality: Elisa’s authenticity and strength—her “planter’s hands,” sensuality, and intelligence—are unwelcome in a world defined by rigid gender norms. The Tinker, as a male outsider, can exploit those qualities without consequence, while Elisa is punished emotionally for daring to reveal them.

Works Cited

Steinbeck, John. The Chrysanthemums. In The Portable Steinbeck, edited by Jay Parini, Penguin Publishing.

LitCharts. "The Tinker Character Analysis in The Chrysanthemums." LitCharts, 2025. LitCharts

LitCharts. "The Chrysanthemums Summary & Analysis." LitCharts, 2025. LitCharts

Notes on Formatting and Context:

This essay is approximately two pages when formatted in standard double-spaced, 12‑point Times New Roman, with 1‑inch margins.

Three embedded quotes from the story are included, each clearly attributed.

The analysis integrates these quotes with insight into the characters’ dynamic.

The Works Cited follows MLA guidelines: author (Steinbeck), title in italics, container title, editor, publisher, and also includes secondary sources consulted.

Let me know if you’d like adjustments—maybe a stronger thematic focus, alternative quotations, or formatting tweaks!

____________________

Some students will take the time to read through the paper to correct grammar and punctuation. They may also fix in-text citations and tweak the Works Cited page to include our textbook.

I teach English composition at a two-year community college. The first paragraph in the Steinbeck short story paper reads like it was written by either a student in their last semester of college, earning a BA in English, or by a graduate student. Punctuation like the use of colons and em dashes also screams: AI-generated!

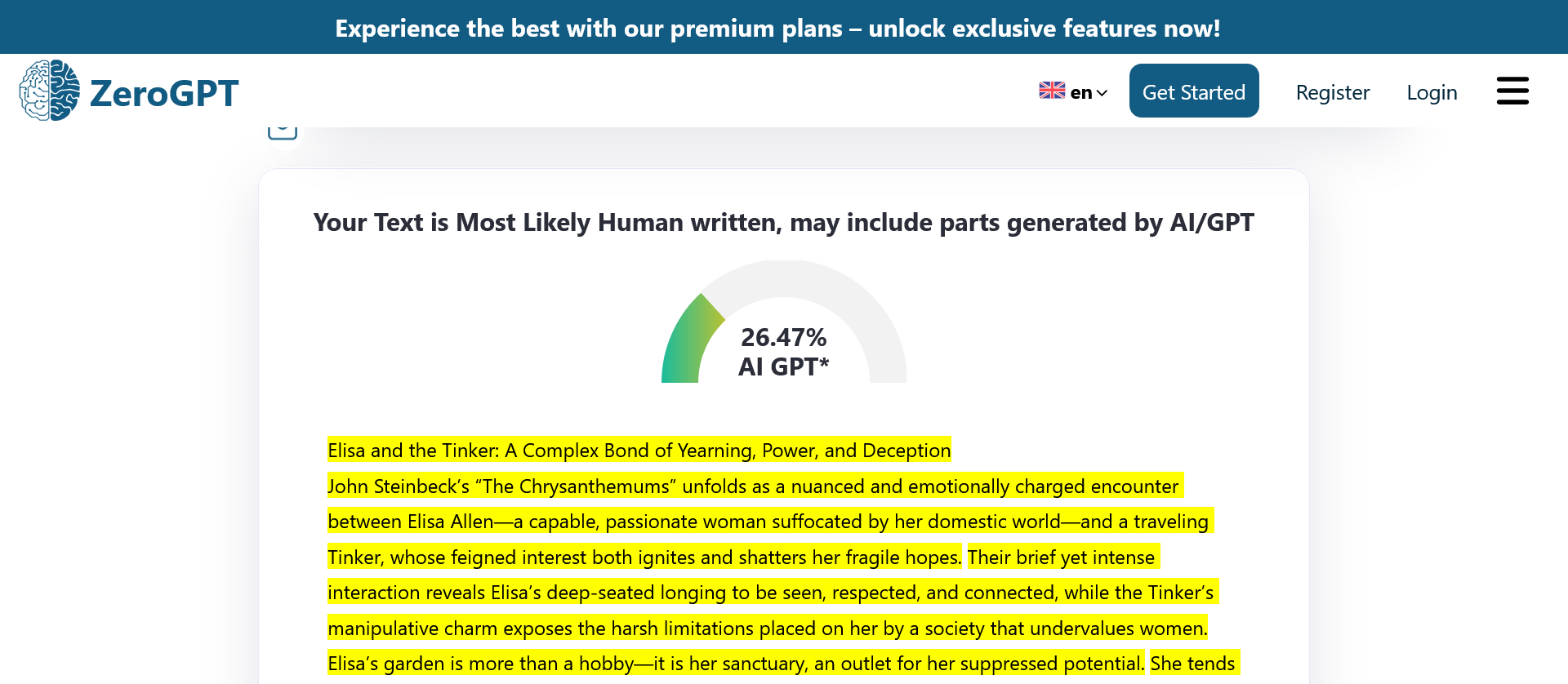

I entered the above paper into ZeroGPT to detect if AI was used. This is what I received in under five seconds:

If this were a student paper, it would be up to me to decide if AI was used to generate the content. Obviously, it was, but I have no proof. And then the question arises: Who made me the AI police? Each semester, I dedicate more time to identifying AI papers than I do to teaching, assessment, and building relationships with students. I have read several articles on the topic of AI in higher education in hopes of finding a solution. Some professors are using the antiquated blue books we wrote in before computers. “I’m going back to pen and paper!” they declare. Others are enlisting their teaching assistants to take painstaking care when grading work, searching for the elusive AI tells. And some, sadly, are retiring early. “What’s the point?” they ask. “Learning and knowledge are dead.”

So, back to the question of cheating. The AI-generated paper on “The Chrysanthemums” is not the product of stealing sentences and paragraphs from authored sources; rather, it is an amalgamation of everything ever written about the short story. In essence, the big AI brain organizes thousands of ideas written and published about this short story. It then incorporates these ideas into a cohesive paper meeting the criteria I entered. Is it cheating? I believe so, and my policy, outlined in my syllabi, explains why:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has many valuable applications. In healthcare, it can assist scientists with data mining and doctors in tailoring treatments for patients. In education, it can help professors monitor student progress and provide an unlimited supply of resources. In manufacturing, it can help perform tasks more efficiently and weigh pros and cons in design. What it can’t do is think for humans. Instead, it uses algorithms to reach an outcome.

You are far more complex than an algorithm. In this class, I am interested in helping you develop your critical thinking skills, ability to synthesize information, and creativity when tackling tough questions. Essentially, I am interested in you as a person and how you think and feel about the world and its people. I cannot assess these things if you choose to use AI or plagiarize work done by others. This said, I do not accept work generated by applications such as ChatGPT, Grammarly, Google Translate, etc. I also do not accept work that is plagiarized (copied) from other sources. Your work must be your ideas.

I am passionate about this topic and have studied AI applications and detectors to spot cheating. I also have a background in English as a Second Language (ESL), bilingual education, and linguistics, which allows me to detect the use of these applications in student work.

If you find that you’re struggling in this class, email me. Sometimes, students plagiarize or use AI when they become overwhelmed or do not understand an assignment. I am available to answer questions to help you succeed in this course.

_______________

For a while, I wanted to point a finger at students. After all, my expectations are clearly stated. But this is a gray area. The recent high school graduates I have as college students today have been glued to screens, clicking buttons as soon as their toddler hands could hold a phone. They are rarely asked to express themselves and are terrified of rejection when they do. Social media has taught them the world can be a cruel and targeted place, and their job is to stay out of the crosshairs. Even knowing this, I feel betrayed when I think I am reaching students, and they take the path of least resistance, submitting AI-generated papers. “Why are you cheating and lying to me?” I want to ask. “Can’t you see I want to share with you the beauty and complexity of stories. I want you to think about history and philosophy, relationships and places far from this small town. I want you to feel pride when earning an A on a paper because you dug deep to share your understanding of a particular piece of writing. I want you to enter the world with the tools and knowledge to make your own decisions. I want you to be self-reliant and able to discern truth from lies. I want you to look up from your screen long enough to step outside and feel the sun on your face or to meet a friend in person for coffee, and then share those experiences in a paper that is solely yours and yours alone. I want you to face AI head-on and shout, ‘I am smarter than you!’”

Our nephew is with us this weekend, deer hunting with my husband, Ron. Trent is a junior at Arizona State University studying economics. I have been teaching for decades and sometimes worry that my perspective is outdated. That I have become the female version of William Henry Devereaux Jr. in Richard Russo’s novel Straight Man, about an English professor who is feeling the pinch of middle age in a vocation that has lost its luster over time. Or, is it simply that he held on too long to his younger self, a man who once had all the answers? In any case, I wanted a young college student’s take on what I see as a dilemma.

“I think AI has some great applications. I use it all the time,” Trent said, and my heart sank. I was Devereaux after all.

“So, can I give you an example of what is going on in my composition and creative writing classes?”

He listened intently and, in the end, he asked,” So, you are asking students to respond to questions about literature using their own ideas?”

“Yes. That’s what I require for all assignments.”

“Well, that’s not original work. Yeah, I would consider that cheating. I use AI very differently in classes that allow it. It has many uses in economics. I can see why you’re struggling with this,” he said.

Vindication washed over me: Ha! I was right! And just as quickly, sadness set in. Have we sold our souls in the name of technology?

Do not be fooled. Artificial Intelligence is an oxymoron like jumbo shrimp or Dodge Charger. There is nothing artificial about intelligence. It begins the moment we enter this world and take in our mother’s scent when placed in her arms. We learn to laugh and cry, signaling our needs. We learn to walk and talk while falling and picking ourselves back up. We learn to hold a crayon and wear big girl underwear. We can’t wait for kindergarten to start, where older kids teach us how to conduct ourselves in the cafeteria and on the playground. Some kids are drawn to bugs, music, or picture books. Some will want to build things, while others will want to take things apart to learn how they work. By the time young adults reach me, their intelligence about themselves and the world we live in is through the roof. “You are real,” I want to tell them. “There is nothing artificial about you. Trust yourself, and I will be here when you have questions. And please, do not cheat. There is too much at stake!”